|

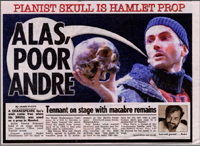

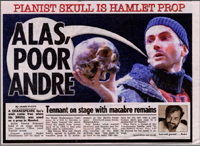

From the

Rochester New York Democrat and Chronicle newspaper on August 15, 1982.

While there are errors (both parents did not die in World War Two; he

was never smuggled to Paris), this Associated Press (AP) posting appeared

in newspapers worldwide. It was this very article that started David

A. Ferré on his 30-year search into the life and times of André

Tchaikowsky.

BBC TV series

"QI" features André's skull - Click

Here

The "Skull" portion of a BBC Radio 3 Broadcast, "A

Study in Contrast" from July 10, 1992, narrated by pianist

David Owen Norris, with Terry Harrison and Peter Frankl (courtesy of

the BBC): contrast_skull.mp3

(UK) TV

broadcast Dec. 2, 2008

channel4_skull_story.mp3

Click

Here for a video Link

Voices: Jon Snow, Stephanie West, Terry Harrison, and

Judy Arnold

(Also on YouTube - Click

Here)

(USA) National

Public Radio

broadcast about the skull

Dec. 3, 2008 npr_skull.mp3

Voice:

Renee Montagne

Click

Here for NPR Webpage

(USA) Public

Broadcasting System (PBS) website for "Great Performances"

has David Tennant's "Hamlet" online. Chapter 18 features André's

skull. Click

Here.

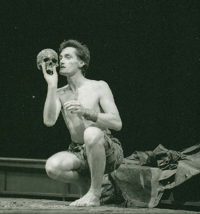

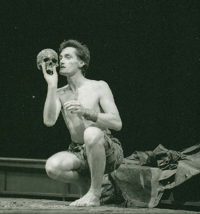

Derek Jacobi

"Hamlet" (1979)

with a plastic skull

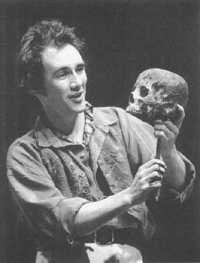

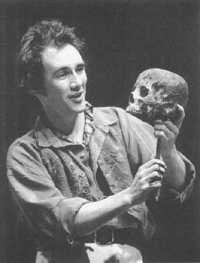

Roger Rees

"Hamlet" (1984)

with a plastic skull

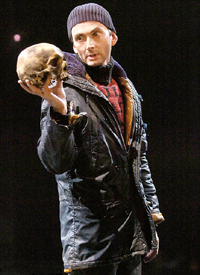

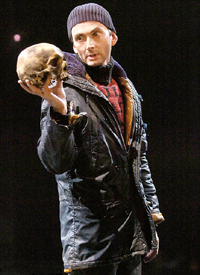

Mark Rylance

"Hamlet" (1989)

with a replica of André's skull

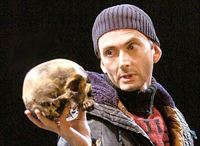

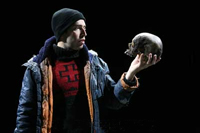

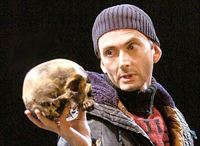

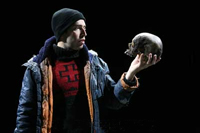

David Tennant

"Hamlet" (2008)

with André's skull

The Telegraph

(Click

Here)

Shakespeare's violated bodies:

Stage and Screen Performance

by Pascale Aebischer

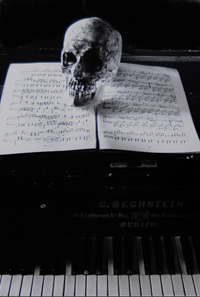

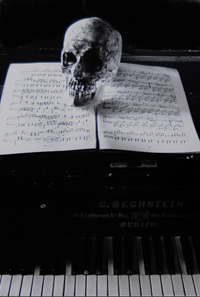

Skull of

André Tchaikowsky

(photo: John

Batten Photography)

Edward Bennett

"Hamlet" (2008)

With André's skull

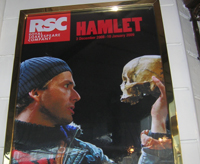

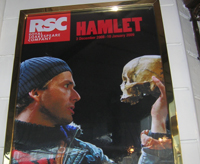

Poster outside

of Novello

Theatre, London (2008-2009)

[Photo: Cecilia Leung]

Novello

Theatre showing RSC's Hamlet (2008-2009)

[Photo: Cecilia Leung]

UPI

News Article (2008)

(Reported to be André's skull)

Skull News in English (2008)

Skull News in Polish (2008)

Skull News in German (2008)

Skull News in Hungarian (2008)

Skull News in Italian (2008)

Skull News in Portuguese (2008)

Skull News in Russian (2008)

Skull News in Spanish (2008)

Skull News in Swedish (2008)

Skull News in Turkish (2008)

Skull News in Ukrainian (2008)

From the Telegraph, Nov. 2009

International

Piano Magazine

Jan/Feb 2009 Issue

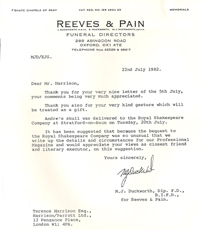

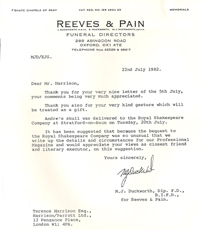

Skull letter

from Funeral Directors (1982)

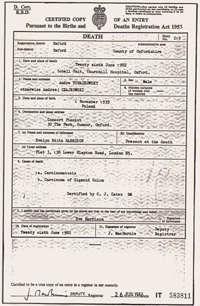

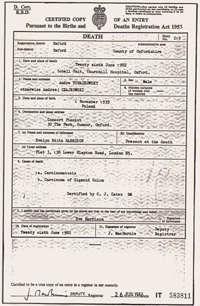

Death Certificate

(1982)

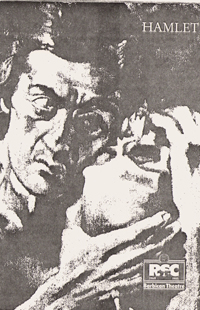

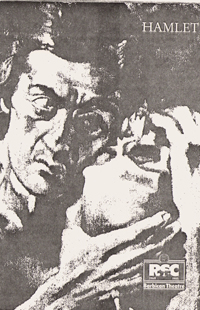

Roger Rees

Hamlet Poster with André's skull (1984-1985)

Portion

of the Will (1979)

Article

in Telegraph Daily

See November 2009 Update

Article in

Jewish Daily Forward

See December 2009 Update

Production

company for Hamlet

DVD

featuring André's skull

Hamlet Graveyard

Scene

with André's skull (2009)

(BBC television broadcast)

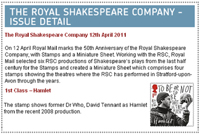

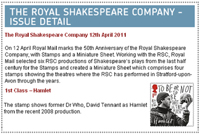

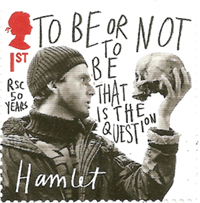

Royal Mail

Issue Detail - Hamlet Stamp with André's Skull

(Click

Here or Image)

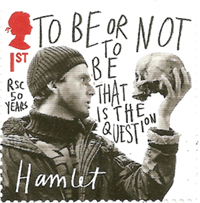

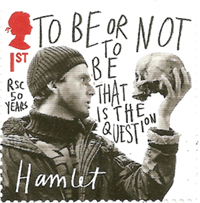

The Hamlet

Stamp

(Click Here or Image)

|

David Tennant

as Hamlet with André Tchaikowsky skull

Recent

Posts (2017)

The following are recent "skull" posts:

The Guardian

(Click

Here)

Secret Jewish History (Click

Here)

André

Tchaikowsky on UK Royal Mail Postage Stamp - April 2011

From the Royal Mail website: "On 12 April [2011] Royal Mail marks

the 50th Anniversary of the Royal Shakespeare Company, with Stamps and

a Miniature Sheet. Working with the RSC, Royal Mail selected six RSC

productions of Shakespeare’s plays from the last half century for

the Stamps and created a Miniature Sheet which comprises four stamps

showing the theatres where the RSC has performed in Stratford-upon-Avon

through the years." As suggested above, one of these six stamps

includes David Tennant (Hamlet) holding the skull of André Tchaikowsky

and, thus, André now appears on a UK Royal Mail First Class Postage

stamp!

Click

Here

for the Royal Mail Website about the Hamlet stamp.

Click

Here or the image for a larger view of the Hamlet stamp.

Skull

"Hamlet" Update - January 2010

From July to November, 2008, the skull used in the graveyard scene in

the Stratford Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC) production of Hamlet was

that of André Tchaikowsky, but the use of the skull was a secret.

When the production moved to London in December, 2008, the secret got

out and the RSC announced they would not use the skull for the London

run. However, this was not the case and the RSC continued to use André's

skull right through to the last performance on January 10, 2009. Thus,

André had his time on stage and was returned to a box in the

RSC prop room, but for only for a short while because the BBC decided

to make a TV dramatisation of the RSC production with David Tennant,

and to once again use André's skull.

January,

2010 - The DVD was released of Hamlet featuring the skull of André

Tchaikowsky, used in Act 5, Scene 1 (graveyard scene). You can view

this scene and scene text using the links below. Be prepared - the opening

of Act 5, Scene 1 shows André's skull in close up.

|

"Skull" Videos on YouTube

|

| Hamlet

Act 5, Scene 1 (part 1) |

Click

Here |

| Hamlet

Act 5, Scene 1 (part 2) |

Click

Here |

| Entire

Hamlet Production |

Click

Here |

| David

Tennant on Hamlet (13:40 to 14:43) |

Click

Here |

| David

Tennant on Hamlet (continued) (0:00 to 2:02) |

Click

Here |

The entire

Hamlet production is also available online on the Public Broadcasting

System (PBS) "Great Performances" website (Click

Here), where the graveyard scene is recorded as Chapter 18 on the

website. This was broadcast by PBS on April 28, 2010.

David

Tennant and the "skull"

'This is our Yorick. He was a Polish composer and pianist called André

Tchaikowsky. And when he died, in the early eighties, he bequeathed

his head to be used in a production of Hamlet with the Royal Shakepeare

Company. He wanted to play Yorick. So here he is. This is André.

He was introduced to us by our director Greg on the first day of rehearsals,

as the final member of the company. There was a variety of reactions

to having a real human head in the production. Some people find it quite

difficult. I must say, personally, I was rather excited by it. It's

one of the clichés of the play now, an actor holding a skull.

And I suppose the trouble with the cliché is that it loses meaning.

But if you are presented with an actual person's skull, a real bit of

human, then Hamlet's speech about Yorick and about staring at the skull

of a man he knew well… it becomes all the more potent when you

are aware that you are holding somebody's head quite literally in your

hands. There he is. André was there. I feel very pleased to have

helped him fulfil his ambition.' (Courtesy: Shakespeare Uncovered -

Original Website Here)

Illuminations

"Hamlet" on DVD - December 2009

Illuminations

is an independent production company and media publisher that specializes

in making and distributing films about the arts. It was Illuminations

that filmed David Tennant as Hamlet for BBC2 television for broadcast

on December 26, 2009. As in the stage production in both Stratford (2008)

and London (2008-2009), the skull of André Tchaikowsky was used

in the graveyard scene for the BBC2 broadcast. This Hamlet production

is available for purchase as a Digital Video Disc (DVD) and is in the

European PAL television format. Click

Here for purchasing information from Illuminations.

BBC

News about the skull

A good summary of the skull, it's history and how it came about (Click

Here).

Story

of the Skull - From the Biography

The following text is from the book,

The Other Tchaikowsky - A Biographical Sketch of André Tchaikowsky,

and describes what is known about the André's donation of his

skull to be used in Shakespeare theatrical productions of Hamlet.

The

Skull Bequest

After André's death, Terry and Eve Harrison went to André's

home to advise his neighbors of the unhappy news. They found a will,

written on October 10, 1979. It seemed a standard document, except for

the end of Clause 13:

13. I

HEREBY REQUEST that my body or any part thereof may be used for therapeutic

purposes including corneal grafting and organ transplantation or for

the purposes of medical education or research in accordance with the

provisions of the Human Tissue Act 1961 and in due course the institution

receiving it shall have my body cremated with the exception of my

skull, which shall be offered by the institution receiving my body

to the Royal Shakespeare Company for use in theatrical performance.

The bequest

of André's skull to the Royal Shakespeare Company was a surprise,

but Terry and Eve were determined that André's last wishes be

honored. Terry telephoned playwright Christopher Hampton ("Les

Liaisons Dangereuses"). Hampton lived in Oxford and they had become

friendly when André decided to undertake an opera based on Hampton's

play, "Total Eclipse." Hampton called a friend at the RSC,

joint artistic director Terry Hands. Terry Hands:

"I

was informed of the bequest immediately after André's death

and asked Christopher Hampton how seriously felt was the request.

It did seem serious. André was passionate about Shakespeare

and had attended many performances at the RSC. We were honoured and

we accepted. It was agreed that when next we played Hamlet, it would

be used."

The funeral

directors at Reeves and Pain who were handling the cremation refused

to remove André's head, and further, they believed such a bequest

was illegal. Terry contacted his legal advisors who in turn contacted

the British Home Office. The Home Office decided the bequest was not

illegal and the RSC could accept the gift. Reeves and Pain asked that

the head be removed by a medical staff member at the hospital before

they picked up the body. This was done. At virtually the last minute,

Reeves and Pain was able to obtain André's remains from the hospital,

sans cranium, in time to prepare his ashes for the memorial service

on July 2. The head was turned over to a museum for processing.

The memorial

service for André Tchaikowsky was announced in a letter from

Terry Harrison:

André

Tchaikowsky will be cremated at the Oxford Crematorium, Bayswater

Road, Oxford, at 11 a.m. on Friday, July 2. We are following André's

wish that the service not be religious. The cremation will be conducted

by Chad Varah, the founder of The Samaritans and a very close friend

of André's. At the beginning of the ceremony we shall have

a performance of André's Trio Notturno which will receive its

world premiere at the Cheltenham Festival on the evening of July 4.

It was recorded for André by the trio he wrote it for Peter

Frankl, Gyorgy Pauk, and Ralph Kirshbaum -- three days before he died,

and it was the last piece of music he heard. At the end of the ceremony

we shall playa recording of the adagio from Schubert's Quintet in

C major for Strings, Opus 163, which André particularly loved.

The genesis

of the skull bequest comes from a conversation between André

and his manager, Terry Harrison. André suggested to Terry that

he would leave his skull to the Royal Shakespeare Company so that they

might have a real skull for Hamlet productions. As Pascale Aebischer

relates in her book, Shakespeare's

Violated Bodies, André's skull might not be used in Hamlet

because the actors always saw André instead of Yorick:

The extend

of the skull’s capacity for extrafictional reference and its

concomitant potential to substantially influence the interpretation

of the scene first became apparent to me when I began my research

on Ron Daniels’s second RSC production [in 1989]. In the middle

of a stack of archival material about the production, I found a memorandum,

dated 9 May 1989, that read: “If André Tchaikovsky isn’t

actually playing Yorick this year, please can we have his skull back

in the Collection for future reference, or whatever you do with skulls

of dead pianists.” The story I managed to piece together from

this point of departure is the following.

In 1980,

André Tchaikovsky, an Oxford-based classical musician, saw

Michael Pennington’s performance of the role of Hamlet in Stratford-upon-Avon.

He was so taken by the macabre dialogue in the graveyard scene that

on his way home to told his companion [Terry Harrison] of his intention

to bequeath his skull to the RSC so that he - or at least a part of

him - might appear as Yorick in a future production of Hamlet. A few

years later, the property department manager for the RSC, William

Lockwood, received a call from an undertaker [M. J. Duckworth for

Reeves & Pain, Funeral Directors, Oxford] who asked whether the

RSC might be interested in the cranium of a deceased client. Horrified,

Mr. Lockwood passed the question on to Terry Hands (at the time the

RSCs artistic director), who promptly accepted the bequest. A mere

ten days later, to Lockwood’s discomfiture and evident delight

of the department’s dog, Mr. Lockwood received a cardboard parcel

containing the freshly processed golden-toothed skull of André

Tchaikovsky. After extensive airing [two years on the roof of an RSC

building], if found a provisional resting place on a shelf in the

property department.

He briefly

left the shelf for a photo-session with Roger Rees for the poster

of Daniels’s 1984 production, but was immediately sent back to

rest, a Fiberglas cast of his cranium taking his place in the theatre.

André Tchaikovsky’s first genuine chance to star as Yorick

came only in 1989, when Mark Rylance started to rehearse the title

role of Hamlet in Daniels’s production. A rehearsal note dated

13 February 1989 records: “Mark Rylance has asked whether it

would be possible to use the real skull that was donated to the RSC

as Yorick’s skull?” The property department complied, and

Tchaikovsky appears to have spent one month in the rehearsal room

preparing the role of Yorick.

On 23

March 1989, however, the first indication of trouble is casually mentioned

in a rehearsal note: “we will be using the real skull for Yorick

but will need a standby in case of accident.” What accident?

Although Tchaikovsky must have been aware that playing Yorick would

entail being “knocked about the mazard with a sexton’s spade”

(5.1.85-6), Rylance’s desire to grant Tchaikovsky’s wish

seems thus to have been paradoxically checked by a simultaneous desire

to honour the dead. Eventually, squeamishness about the rough handling

of real human remains seems to have triumphed. Claire van Kampen,

the production’s musical director and later Mark Rylance’s

wife, remembers that:

“As

a company, we all felt most privileged to be able to work the gravedigger

scene with a real skull... However, collectively as a group we agreed

that as the real power of theatre lies in the complicity of illusion

between actor and audience, it would be inappropriate to use a real

skull during the performances, in the same way that we would not

be using real blood, etc. It is possible that some of us felt a

certain primitive taboo about the skull, although the gravedigger,

as I recall, was all for it!”

On 7

April 1989, a last rehearsal note records how Tchaikovsky was finally

defeated in his quest for on-stage remembrance, although touchingly,

the understudy to replace him was to be an exact look-alike: “We

are no longer using the real skull as Yorick but would like to use

a cast of it (complete with teeth).”

In spite

of his early retirement to the shelf in the property department, Tchaikovsky’s

presence in the rehearsal room left a deep mark on the production’s

interpretation of the tragedy’s concluding moments. The graveyard

scene opened with the gravedigger (played by Jimmy Gardner, the actor

implicitly accused by van Dampen of having an inappropriate attitude

towards Tchaikovsky’s remains) using the skull as a pawn with

which to illustrate the legal intricacies of Ophelia’s inquest,

Rylance’s accusatory tone when his Hamlet commented that, “That

skull had a tongue in it, and could sing once” (5.1.74), while

ostensibly referring to the (at that point anonymous) fictional owner

of the skull within the world of the play, was charged with an additional,

reproachful meaning in its reference to the two actors’ disagreement

over the proper treatment of Tchaikovsky’s head.

When

quizzing the gravedigger about the decomposition of bodies, Hamlet

jumped into the grave to get a closer look at it all. It was thus

in the grave that was shortly to be Ophelia’s that he was handed

Yorick’s skull atop the Gravedigger’s spade, when as eleven

years later in Lester’s hands, it became a puppet that was mused

over by a wistful Hamlet who strained to hear Yorick’s silent

answers to his question, making the skull come back to life as his

chopfallen interlocutor. The aimless existential despair of Rylance’s

Hamlet was here converted into focused, intense mourning and tenderness

for the skull. Yorick seemed to have taken over the roles of the Ghost

and Polonius as the old mole/perturbed spirit/foolish prating knave

in the grave hovering on the brink between life and death, remembrance

and oblivion.

Hamlet’s

composure in his confrontation with Laertes in the graveyard seemed

to spring out of this encounter with death and memory in the shape

of Yorick, whom he lovingly carried into the next scene, his cradling

of the cranium mirroring Laertes’s mournful rocking of Ophelia’s

body in the grave. Yorick was casually tucked under Hamlet’s

arm during his dialogue with Osric, deposited on the floor for Hamlet’s

handshake with Laertes and finally carefully set down on a mantelpiece,

where Hamlet “turn[ed] it so that its eyeless sockets faced the

action, as a talisman during his duel with Laertes.” How closely

this performance choice was linked to Tchaikovsky’s presence

in the rehearsal room is clear from van Kampen’s comment that

“Probably it was this very realness [of the skull] that fired

Mark [Rylance]’s imagination to believe that the power of Hamlet’s

father’s old jester was so great that, as a kind of talisman,

or fetish, Hamlet takes him through Act V to his, Hamlet’s own

death.”

The skull

of Tchaikovsky and/or Yorick thus had the effect of doubling Hamlet’s

quest for revenge and confrontation with death with Mark Rylance’s

desire to honour the last will of Tchaikovsky, who became the company’s

own uncomfortable memento mori and its Ghost clamouring for posthumous

remembrance. Because the property disturbingly kept its extrafictional

and extratheatrical identity as the property (in the sense of ownership)

of André Tchaikovsky the pianist, it resisted the company’s

attempted to appropriate it as an accessory. Instead, it became an

“improper property” that defied theatrical decorum.

In a

company such as the RSC that generally uses non-Grotowskian techniques,

decorum dictates that theatrical signs which pertain to the human

body (by they objects such as bones or blood or physical expression

such as pain or orgasm) should stay at a distance from their referent,

a distance which, as Claire van Kampen put it, is bridged by “the

complicity of illusion between actor and audience.” Only when

the real skull, with its real identity as André Tchaikovsky’s

head, was replaced by an identical-looking fake was the company able

to adopt the property as an iconic sign that could stand primarily

for Yorick rather than Tchaikovsky.

Aebischer's

guess that it was the 1980 RSC Hamlet production that stirred André

skull bequest could not be correct because the Will was signed in October,

1979. A better guess would be the 1979 production at the Old Vic Theatre

in London, with Derek Jacobi as Hamlet.

Hamlet

retained Yorick's skull throughout subsequent scenes in the 1989 poduction,

and it was eventually placed on a mantelpiece as a "talisman"

during Hamlet's final duel with Laertes.

Typical

of the André Tchaikowsky obituary notices is one by Alan Blyth

of The Daily Telegraph, which appeared on June 30. (All of the obituary

notices contained errors, the most common of which were that both of

his parents were killed during the war and that he was smuggled out

of Poland to Paris.)

André

Tchaikowsky, pianist and composer, died on the weekend in Oxford.

He was 46, and although ill since the beginning of the year, he recovered

sufficiently to resume playing in May. He also managed to complete

an opera based on "The Merchant of Venice."

He was

born in Warsaw on November 1, 1935. Both his parents were killed under

the Nazi occupation, but he was smuggled out to Paris. After the War

he studied there and also in his homeland before winning the coveted

Chopin Prize in the Polish capital in 1955, completing his studies

with the Polish pianist, Stefan Askenase. His British debut was in

1958. He decided to make his home in Britain while continuing to build

an international career as a pianist with a wide-ranging repertory.

His particular loves were Bach and Mozart.

Over

the past 20 years, he devoted about half his time to composing. His

list of works included the Piano Concerto written for Radu Lupu and

given its first performance by him 10 years ago. Apart from his opera,

Tchaikowsky had also completed a Trio Notturno for piano trio. It

will be given its premiere at the Cheltenham Festival on Monday.

His playing

tended to be ebullient and full of an instinctive feeling for the

style of the composer. He was an inveterate follower of his fellow

pianists and until his last illness could be seen at practically every

recital of note in London.

In Germany,

a Frankfurt newspaper reported:

Composer

and Pianist -- The Death of André Tchaikowsky

The well-known

and highly regarded pianist André Tchaikowsky died from cancer

on June 26 at the age of 46, near his home in Oxford. He was one of

the most talented pianists of his generation, and a Mozart player

of the first rank, with individual and subjective interpretations

in comparison to the "classic" interpretations. Tchaikowsky

gave to his performances a rare feeling of color and contour. His

Chopin playing was witty, often with strong rubato and changes in

tempi -- sometimes a bit over the top -- but always revealing the

structure of the composition. To summarize, André Tchaikowsky

thought musically first, and pianistically second.

In Poland,

André's passing was memorialized with a series of seven radio

programs of two hours each. The programs, organized by Jan Weber of

Polish Radio, included André as pianist, and André as

composer, interspersed with interviews of his friends, in particular,

with Halina Wahlmann-Janowska, who read portions of the letters she

had received over the many years of their correspondence. Although André

never returned to Poland after 1956, he remained well-known there, and

interest in both his piano playing and composing has remained high.

The museum

entrusted with André's skull returned it, processed, to Reeves

and Pain on July 18. Reeves and Pain then reported to Terry Harrison

on July 22, "André's skull was delivered to the Royal Shakespeare

Company at Stratford-Upon-Avon on Tuesday, 20th July." Up to this

point, the bequest had remained private. Mr. Duckworth, funeral director

at Reeves and Pain, was interested in publishing the story of André's

skull in a funeral directors' professional magazine and asked Terry

Harrison for his opinion. Terry responded on August 4:

Eve and

I have no objections to your reporting the bequest of André's

skull in your professional magazine. However, could you let me know

whether you would particularly want to use his name, or were you thinking

the deceased would be nameless? My present thought is that we would

not mind his name being used, but I would just like to think about

that point a little more.

Terry wasn't

permitted the luxury of further thinking. Someone informed the press

about the strange bequest and the story hit, first, the London papers,

then the international news services, in particular the Associated Press.

The news of André's skull quickly spread worldwide, from the

US to Australia and beyond. Mr. Duckworth wrote an immediate letter

to Terry Harrison assuring him that Reeves and Pain was not responsible

for the news leak. Terry responded on August 24:

I was

away for two weeks so missed the news escaping about André's

skull. My secretary Claire heard the broadcast of this news item on

Independent Radio and she told me she didn't think it was offensive.

I would have preferred that the news had not come out, but quite honestly

I don't think it is particularly bad that people know, as André

was rather an extraordinary person and it would have touched his sense

of whimsy to know that he caused some consternation. So don't worry

about the matter. I presume it must have been leaked by somebody connected

with the hospital.

A sampling

of the newspaper articles suggests the stir caused by André’s

final eccentricity. From

The Times in London on August 14:

Pianist’s

Skull Waits in Wings

Mr. André

Tchaikowsky , the Polish-born concert pianist, asked in his will that

his skull be given to the Royal Shakespeare Company for use in future

productions of Hamlet. Mr. Michael Duckworth, a partner in Reeves

and Pain, an Oxford firm of undertakers, said Mr. Tchaikowsky, who

died at his home near Oxford in June, apparently had a lifelong ambition

to be an actor. The RSC said the skull had been delivered and would

be stored. The company does not have plans to stage "Hamlet"

in the immediate future.

From The

Daily Telegraph in London on August 14 by Anthony Hopkins:

Hamlet

Gets a Skull in Bequest

"This

same skull, sir, was Yorick's skull, the King's jester." "Alas,

poor Yorick. I knew him, Horatio: a fellow of infinite jest."

-- Hamlet

A man

who nursed a lifelong ambition to go on the stage has bequeathed his

skull to the Royal Shakespeare Company for use in productions of "Hamlet."

Mr. André Tchaikowsky, a concert pianist and composer, died

at his home at Cumnor, near Oxford, in June, aged 46. Now his skull

has been delivered in a box to the RSC. A spokesman for Mr. Terry

Hands, the RSC's joint artistic director, said that Mr. Tchaikowsky

had been an avid Shakespeare enthusiast with a love of the stage.

"We were staggered when the executors of the Will asked if we

wanted the skull."

Mr. Michael

Duckworth, a partner in the undertaking firm of Reeves and Pain, said:

"Mr. Tchaikowsky's friends and executors desperately wanted to

fulfill his wishes and we are here to do what we can for our clients."

The RSC

has no immediate plans for a production of "Hamlet." "But

when we stage it again we hope to use Mr. Tchaikowsky's skull,"

said a spokesman. Meanwhile, the skull, still in its box, is in store

at the RSC's headquarters in Stratford-upon-Avon.

In 1984,

the Royal Shakespeare Company did produce "Hamlet." Actor

Roger Rees (Hamlet) remembers the situation:

''I'm

afraid André's skull was not used directly on stage for the

actual production of 'Hamlet.' We found long ago that a real head

is too fragile to be used in the rather rough-handling gravedigger

scene, so we use plastic skulls which hold up better. However, the

RSC was delighted to have a real skull for their various needs. When

they first got the skull, they put it outdoors for a few months, in

the sunlight, to dry it out completely and to bleach it bone white.

"The

skull was used as part of the 'Hamlet' poster for the 1984 production

in Stratford and the 1985 production in London. I had to pose for

this poster, two hours a day, for three days running. In my hands,

I hold a skull, and that's André's skull. The artist was Phillip

Core and he remarked that it must be a real skull because it still

had bits of gristle around the ear ports, and various places. So indirectly,

André's skull was used for Hamlet."

André,

of course, had never wanted to be an actor on the stage. He was, instead,

a great enthusiast of theater and loved the works of Shakespeare. But

what was the real reason for the bequest? When his friends heard about

the skull, no one seemed surprised. "Typical André,"

was the comment most often heard. Michael Menaugh remembers:

"Unfortunately,

the fact of the skull will not go away for any of us. It is something

that ultimately we have all to come to terms with, to reconcile with

the André we knew and loved. I don't think André realized

the effect such a bequest would have, both on his friends and on his

own reputation. André didn't always understand that the world

of ideas and the world of real people, real reactions and real events

just did not coincide.

"He

had spoken to me of leaving his skull for the RSC to use in Hamlet

back in 1966 when he wrote the music for my Oxford Hamlet. In my undergraduate

way, I thought the idea wonderfully entertaining. When a great actor

may hold the skull of a real man, a real man who 'set the table on

a roar,' a wonderful man who had his 'gibes and gambols and songs,'

when that great actor says, 'A fellow of infinite jest, of most excellent

fancy,' might not that electrifying flash of truth (transmitted by

the actor) light up the play? André would have liked that idea,

I think."

November

2008 to January 2009 Update

After more than 25 years in the wings, André's wish to appear

in Shakespeare's play Hamlet as the skull of Yorick was realized

at last. The Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC) 2008 production of Hamlet

used André's skull from July to November in Stratford, but then

declined to use it when the production moved to London in December,

2008, because the secret use of the skull had been revealed. From the

Telegraph

newspaper (London), November 22, 2008, an (abridged) article by

Vicki Reid:

David

Tennant: from Doctor Who to Hamlet

There

is one intriguing story about the production that among all the mayhem

has managed to remain untold. During the run, the company has played

each performance with an extra member. On the first day of rehearsals

the cast was introduced to a real skull - that of André Tchaikowsky,

a Polish composer who settled in Oxford, where he continued to compose

and visited Stratford often.

He died

of cancer in 1982 at the age of 46, and bequeathed his skull to the

RSC, where it sat in a box in the props department, before Doran decided

he was going to use it. He hoped it might bring the cast closer to

the text: 'This play has to touch something in us - we have to face

our own mortality, and Hamlet has to face that. It was sort of a little

shock tactic, though, of course, to some extent that wears off and

it's just André, in his box.'

Doran

didn't want the story to get out before Hamlet opened. 'I thought

it would topple the play and it would be all about David acting with

a real skull. 'Tennant was delighted to be fulfilling Tchaikowsky's

wishes. 'When I heard he had done this,' he says, 'I thought, that's

brilliant, that's what I'm going to do, but apparently you can't any

more, the law's been changed.'

David

Smith wrote for the Guardian

and The Observer on Nov. 23, 2008:

Pianist's

skull plays the jester

'Alas,

poor Yorick,' laments Hamlet, holding up the skull of the King's late

jester. The gravedigger scene in the hit production of Hamlet starring

David Tennant can claim unprecedented realism. For each night Tennant

is holding aloft a genuine skull.

The extra

cast member is André Tchaikowsky, a Polish concert pianist

and composer who, after his death from cancer in 1982, bequeathed

his skull to the Royal Shakespeare Company in the hope of achieving

his acting dream. The skull sat in a box in the props department,

virtually untouched for 25 years, until director Gregory Doran retrieved

it for its stage debut.

Tchaikowsky's

posthumous performance, which it is safe to assume makes up in consistency

what it lacks in expressiveness, was kept secret when the show opened

in Stratford-upon-Avon, where there was already massive hype around

Doctor Who star Tennant.

Tchaikowsky

emigrated from Poland to Oxford in 1939, when he was four, and was

a frequent visitor to Stratford. He died at the age of 46 and left

a will requesting that his organs be used for medical purposes, 'with

the exception of my skull, which shall be offered by the institution

receiving my body to the Royal Shakespeare Company for use in theatrical

performance'.

The Home

Office decided the bequest was not illegal and the RSC could accept

the gift. The company put the skull outdoors for a few months so the

sunlight would dry it out completely. Actor Mark Rylance spent a month

rehearsing with the skull when he played Hamlet in 1989, but 'eventually,

squeamishness about the rough handling of real human remains seems

to have triumphed.'

Seventeen

years later, however, Doran decided to take the plunge. 'It was sort

of a little shock tactic... though, of course, to some extent that

wears off and it's just André, in his box,' he said.

Debbie

Waite wrote for the Oxford

Mail on Nov. 26, 2008:

Skull

gets starring role

An Oxford

man has achieved his dying wish to have his skull used in Hamlet —

26 years after he donated it to the Royal Shakespeare Company. Concert

pianist André Tchaikowsky’s skull lay unused in a box,

because actors shied away from performing with it on stage. But now

it has been revealed Dr. Who actor David Tennant held the skull aloft

during the famous 'Alas, poor Yorick' scene in a 22-show run at the

theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon.

Mr. Tchaikowsky,

a Holocaust survivor who came to Oxford after the Second World War,

made it a condition of his will to give the body part away in the

hope it would be used in a theatrical performance. Despite being used

in rehearsals, the skull had never been in a stage performance until

Hamlet director Greg Doran retrieved it from its protective box in

the RSC’s climate-controlled archives.

The play

moves to London next week but it is yet to be decided if Mr. Tennant

will use the skull there. Mr. Tchaikowsky’s family were delighted

his skull had at long last been used on stage. Mr. Tchaikowsky, who

lived in Cumnor, regularly attended performances in Stratford before

his death from cancer at the age of 46. David

Howells, curator of the archives, said:

“It

has never been used on stage before. In 1989 the actor Mark Rylance

rehearsed with it for quite a while but he couldn’t get past

the fact it wasn’t Yorick’s, it was André Tchaikowsky’s.

That, and the fear of an accident and it being slightly macabre,

was why they decided not to use it and used an exact replica.”

The RSC

had to apply for special permission to use the skull from the Human

Tissue Authority, as it is less than 100 years old. Mr. Doran, who

made the decision to use it, explained why he didn’t want anyone

to know. He

said:

“I

thought it would topple the play and it would be all about David

acting with a real skull. It was sort of a little shock tactic,

though, of course, to some extent that wore off and it was just

André, in his box.”

In Hamlet,

a gravedigger unearths the skull of jester Yorick, prompting Hamlet

to deliver the line: “Alas, poor Yorick! I knew him, Horatio:

a fellow of infinite jest, of most excellent fancy.” Dave

Ferre, a friend of the Tchaikowsky family, said: “That was André’s

dream and this is great news. The family will be pleased.”

Richard

Faulks, the current manager of the Reeves and Pain Funeral Directors

in Oxford, which dealt with Mr. Tchaikowsky’s request, was surprised

to hear about the intriguing tale. He said:

“Unfortunately

the funeral director Michael Duckworth is no longer with us, but

I have been back through our records and we still have the forms

relating to Mr. Tchaikowsky. It has been very interesting reading

about him – he sounds like quite a personality. We’re

delighted to learn that his dying wishes have at last been realised.”

From the

Associated

Press by writer Robert Barr:

Human

skull used in British Hamlet production

LONDON

(AP) - A Polish pianist has made his stage debut in Britain, 26 years

after his death. André Tchaikowsky's skull featured in performances

of "Hamlet" by the Royal Shakespeare Company between July

and November [2008], company spokeswoman Nada Zakula said Wednesday.

It was the first time the skull was used in a performance - his expressed

wish - though the company had used in rehearsals since it was donated

in 1982.

Tchaikowsky's

1979 will had asked that his skull be offered to the Royal Shakespeare

Company "for use in theatrical performance." "We hope

that he would have been pleased that his final wish has been realized,"

company curator David Howells said. It was unclear if the skull would

be used when the company's production moves from its base in Stratford-upon-Avon

to London on Dec. 3, Zakula said.

Tchaikowsky,

a fan of William Shakespeare's plays, had finished orchestrating all

but 24 bars of his operatic adaptation of "The Merchant of Venice"

when he died from stomach cancer on June 26, 1982. News of his unique

bequest became known soon after. "He was passionate about Shakespeare

and attended many performances," Terry Hands told the AP in 1982

when he was joint artistic director of the company. "We are honored

by his bequest."

Andrzej

Czajkowski was born in 1935 in the Polish capital of Warsaw as Robert

Andrzej Krauthammer, but was given his new name on false identity

documents used to smuggle him out of Nazi-occupied Warsaw in 1942,

according to a Web site dedicated to the musician.

December

2008 Update

Once the RSC had made the decision to not use the skull in the London

Hamlet production, other news articles appeared. [Note that the RSC

actually continued to use André's skull.] Typical is that from

this December 3rd, 2008 article posted on Yahoo

News:

Skull

dropped after secret revealed

A human

skull will no longer be used in the Royal Shakespeare Company's (RSC's)

Hamlet in case it distracts the audience, the theatre company said.

The skull of Polish pianist André Tchaikowsky was used throughout

the play's recent run in Stratford-upon-Avon, but the unusual prop

will be dropped when it opens in London's West End, the RSC said.

Audiences

in Stratford were unaware the skull in the play belonged to the pianist,

who had bequeathed it to the RSC in 1982 for this purpose, a spokeswoman

said. But the secret spilled out when actor David Tennant, who plays

Hamlet, revealed it in a newspaper interview.

The RSC

told Channel 4 News that now the secret is out, it would be "too

distracting for the audience" if the skull was used.

Substituting

the real skull for a fake one will also stop the RSC having to gain

permission from the Human Tissue Authority, which it needed before

using the real one in Stratford, the spokeswoman added.

"We

never planned to use the real one in the London run," she said.

In the

Stratford production, Tennant held the skull aloft in the "Alas

poor Yorick" scene of the play, fulfilling the dying wish of

Mr. Tchaikowsky - a Polish Jew who escaped the Holocaust but died

of cancer aged 46.

His former

agent and friend Terry Harrison told Channel 4 News he was "disappointed"

by the decision to abandon the real skull.

The Telegraph

reports David Tennant out until at least Christmas and undergoes surgery

for a back problem. He is replaced by Edward Bennett for all of December.

However, on January 4th, 2009, Tennant returns for the last 6 days of

performances to superlative reviews.

November

2009 Update

From the Telegraph of November

24, 2009:

David

Tennant to revive partnership

with real skull for BBC's Hamlet

David

Tennant is to revive his partnership with a real human skull for a

new BBC film version of Shakespeare's Hamlet. The skull had starred

in a stage run of the classic production last year after pianist Andre

Tchaikowsky left his remains to the Royal Shakespeare Company in the

hope it would be used on stage. Now it is being used in a TV dramatisation

of the RSC production to be screened this Christmas.

The boss of the RSC admitted that the company secretly used the skull

during the play's London run, despite the company saying at the time

it was to use a fake. Tennant held the skull on stage during the famed

''Alas, poor Yorick'' scene for more than 20 performances at the Courtyard

Theatre, in Stratford-upon-Avon. The outgoing Doctor Who star was

lauded for his performance in the production and it has now been filmed

for BBC2.

Greg Doran, who directed the stage and TV versions said: ''Yes, Andre

appears in the film - as in fact he did throughout both the Stratford

and the London runs.'' He explained: ''I didn't allow news that he

transferred to London to be leaked out, as we did not want audiences

to be unnecessarily distracted by what had then become a bit of a

news story.

''Andre Tchaikowsky's skull was a very important part of our production

of Hamlet, and despite all the hype about him, he meant a great deal

to the company.

''Yorick's skull, and Hamlet's lament to him, is probably one of the

most famous icons in Shakespeare, and one most frequently satirised

and misquoted. It was through Andre that the company tried to get

beyond those clichés, to investigate something deeper.

''You can't hold a real human skull in your hand and not be moved

by the realisation that your own skull sits just beneath your skin,

that you will be reduced to that state at some stage. That is what

Yorick's skull does to Hamlet. It reminds him of the very real presence

of Death in Life. Andre's skull was a profound momento mori, which

perhaps no prop skull could quite provide.''

Composer and concert pianist Tchaikowsky died of cancer in 1982 at

the age of 46, donating his body for medical science. But he also

requested that his skull be offered to the RSC to be used on stage.

Although it had been used in rehearsals, actors did not feel comfortable

using his head in front of an audience. Mark

Rylance used a cast of Tchaikowsky's skull 20 years ago after initially

practising his performance with the real thing. The musician's remains

then went back to a box until the skull was used by Tennant. It had

to be given a special license for use and a stand-in had to be used

until permission was given.

Doran said: ''When the Human Tissues Authority (HTA) license had not

arrived by the evening of the Dress rehearsal in Stratford last July,

and we had to place Andre back in his box, our Theatre Collections

Curator, David Howells, allowed us to use another skull he had in

the collection, which as it was more than 100 years old, did not come

under the jurisdiction of the HTA.

''It was the skull used as Yorick by Edmund Kean in 1813. A piece

of theatre history happened that night on the Stratford stage as David

Tennant, a 21st century Hamlet, stared into the empty eye sockets

that a nineteenth century Hamlet had used. For those of us watching,

a little shiver of connection occurred.''

Doran, who is also chief associate director of the RSC, added: ''I

suspect Andre would have been amused by the fact that his cranium

became a question on Have I got News for You?, but his bequest to

the RSC was deeply sincere. 'I hope other productions may, with the

greatest respect for Andre, use the skull as he intended it to be

used, for precisely this purpose.''

December

2009 Update

From the Jewish Daily Forward of December

8, 2009 by Benjamin Ivry:

'Alas,

Poor Andrzej': The Strange Case

of Tchaikowsky's Skull

The admission

by London’s Royal Shakespeare Company that, despite previous

disavowals, a production of “Hamlet” featured not only Dr

Who actor David Tennant, but also a real human skull onstage —

as Hamlet’s deceased friend the jester Yorick — brings the

donor of that skull back into the limelight.

The Polish-Jewish

pianist Andrzej Czajkowski (who performed as André Tchaikowsky),

born Robert Andrzej Krauthammer in 1935 bequeathed his skull to the

Royal Shakespeare Company to be used as Yorick after he died prematurely

of colon cancer at age 46. Until the most recent “Hamlet,”

no production had the kishkas to do so, and even now, the theatre

(deceptively, as it turned out) claimed to withdraw the skull after

it proved a “distraction” to audiences, supposedly replacing

it with a plastic replica.

In fact,

Czajkowski’s skull was used all along, including in a soon-to-be-seen

BBC

filmed version of the play. Czajkowski, a Warsaw Ghetto survivor

and greatly talented performer and composer (whose few recordings

are all available for online listening at the tribute site andretchaikowsky.com)

thus has a weird posthumous triumph, which ranks him as a pianist

comparably gifted to, but even more eccentric than, Glenn Gould.

Czajkowski’s

spirited, mysterious recordings of Mozart; dazzling Chopin; witty

Haydn; and warm-hearted Schubert won many admirers, including Arthur

Rubinstein, an early mentor. Yet most were ultimately turned off by

his oddball behavior, which included erratic attendance at scheduled

performances and recording sessions, and when he did show up he would

pull stunts like at one concert, improvising an endlessly percussive,

out-of-style Bartok-like cadenza to a Mozart concerto until the unnamed

conductor shouted “Enough!” and made the orchestra play

loudly to cut him off.

When

challenged about such off-putting deeds, Czajkowski would refer to

the difficulty of his childhood, when he was smuggled out of the Ghetto.

By the end of his life, too, the social repressiveness of Thatcherism

in the UK must also have irked Czajkowski, who led a flamboyantly

gay life. An intermittently gifted composer, Czajkowski’s best

works, like his “Trio

Notturno” allowed him to express some of the darker inner

aspects.

Apart

from his genuine devotion to Shakespeare and particularly “Hamlet,”

Czajkowski’s macabre donation may be seen in the optic of this

darkness, a sort of desperate theatricality visible in other Polish

creators like the author Tadeusz Borowski, an Auschwitz survivor.

Fortunately, Czajkowski’s artistry has survived magnificently,

and he will be remembered for what went on in his head not just because

of his polished up headbone on stage.

|